-----

March: Book Two is the second volume of Representative John Lewis’s graphic novel memoir, co-written with his aide Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell. March: Book One was a critically acclaimed bestseller and received the 2013 Coretta Scott King Honor Book Award from the American Library Association and was named one of the best books of 2013 by USA Today, The Washington Post, Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, School Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, The Horn Book, Comics Alliance, and others. Book Two promises equal success.

|

| March: Book Two (Top Shelf) |

BOOK OVERVIEW

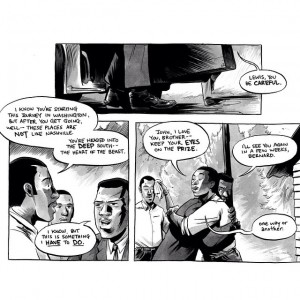

March: Book Two begins with the SNCC’s success at integrating lunch counters in Nashville and their plans to go further. Through Lewis’s recollections, Aydin’s direction, and Powell’s art, we literally become active viewers as the following events unfold:

- Nashville’s nonviolent protests trying to enter movie theaters;

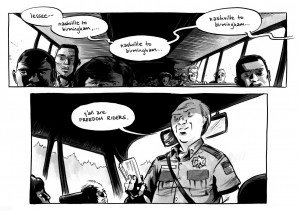

- CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) sponsored Freedom Ride to demonstrate how effectively the Supreme Court Decision of Boynton v. Virginia — which outlawed segregation and racial discrimination in busses and bus terminals in the previous year — was being upheld (or not);

- SNCC (Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee)’s “Operation Open City,” designed to promote free employment practices;

- SNCC’s decision (after discussions with Attorney General Robert Kennedy) to register Black voters;

- SNCC’s change in leadership and conflicts over tactics;

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s SCLS Birmingham Campaign; and

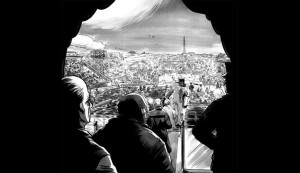

- the March on Washington on August 28, 1963

- Attorney General Robert Kennedy and his aide, John Seigenthaler (to whose memory the book is dedicated);

- Bayard Rustin, organizer of the March on Washington;

- The Big Six:

- A. Philip Randolph (founder of The Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters and influential Civil Rights and Labor organizer),

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.,

- Roy Wilkins of the NAACP,

- Jim Farmer of CORE,

- Whitney Young of the Urban League, and

- John Lewis of SNCC.

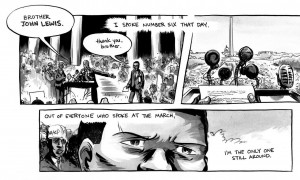

The language alone is worthy of discussion (see below for details). The story weaves back and forth almost effortlessly between events of the 1960s and the historic inauguration of Barak Obama. Lewis shares famous quotes and snippets of speeches, while relaying his story with quotes, metaphors, and descriptions. The art and page design are instrumental in weaving the story pieces together as a whole and making this tumultuous period in our history come alive.

In March: Book Two,

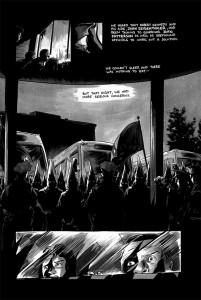

Powell’s deftly uses black and white contrast, sharp angles, and

fonts to relay violent emotions. This is then paired and contrasted with

soft, sloping grays for the gentler intervals. We see Black and White

protesters treated with equal respect and drawn with soft rounded

strokes, while White Southern agitators and Ku Klux Klan members are

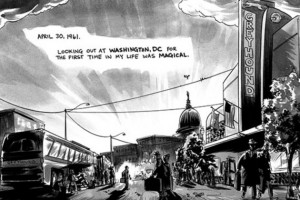

drown in chilling, brutal, angular strokes. There are beautiful

wide-angle shots establishing historic locations, and extensive use of

black and white juxtapositions to relate Lewis’s personal turmoil and

the drama of these famous and infamous events. Lewis, Aydin, and Powell

relay the story in visual and verbal metaphors that are breathtaking.

In March: Book Two,

Powell’s deftly uses black and white contrast, sharp angles, and

fonts to relay violent emotions. This is then paired and contrasted with

soft, sloping grays for the gentler intervals. We see Black and White

protesters treated with equal respect and drawn with soft rounded

strokes, while White Southern agitators and Ku Klux Klan members are

drown in chilling, brutal, angular strokes. There are beautiful

wide-angle shots establishing historic locations, and extensive use of

black and white juxtapositions to relate Lewis’s personal turmoil and

the drama of these famous and infamous events. Lewis, Aydin, and Powell

relay the story in visual and verbal metaphors that are breathtaking.Finally, while Lewis introduces us to the giants of the Civil Rights Movement, he never loses touch with the fact that the real heroes were those who sacrificed their goals, their times, and sometimes their lives to advance civil rights. Furthermore, while Lewis was a key player, he modestly downplays his own role in the events. As a result, the book feels real and we feel like we are there with the participants, looking on and urging them forward.

In short, Lewis’ story is told through gentle narration and vibrant art in a way that empowers us to relive it with him. As a result, readers better understand the social unrest of the early 1960s, the growing pains of the Civil Rights Movement, and the increasing need of coordination among local, state, and federal governments to address these issues.

Throughout March: Book Two, Lewis, Aydin, and Powell relay:

- The effects of segregation and the painful and all-too-gradual upheaval of the Jim Crow laws in 1960s;

- The power and struggles of social gospel and non-violent protest in times of civic unrest;

- The growing pains of the Civil Rights Movement, during which some wanted to meet violence with violence, forgoing their earlier nonviolent dictum;

- The fights fought and barriers overcome by Black and White champions of the Civil Rights;

- The power of the peoples’ voice in a democratic republic;

- The powers and limits of local and national government, especially in times of civic unrest;

- The different ways people find the courage to stand up and fight for their rights;

- The power words can have, be they in print or oratory, as well as the power image can play in communicating passions, events, and perspectives.

- Chart the progress of the Civil Rights movement through March Book One and Book Two. Discuss:

- What was gained?

- What was lost?

- What were the costs to states/cities/individuals?

- What were the pivotal decisions made that helped shape the changing political and social landscapes?

- Research the Supreme Court Decision in Boynton v. Virginia. Compare Lewis’ account to accounts found in newspapers and magazines of the time.

- Research and discuss CORE’s Freedom Ride. (See below for links to relevant resources.) Discuss:

- What participants went through just to get there;

- Different ways people reacted and reported this incident (newspapers, magazines, personal accounts).

- What were some of the social and political issues that city officials faced as the Riders approached their jurisdiction?

- Research, present and discuss the lives and roles of the Civil Rights Movement leaders mentioned in this book:

- James Farmer (CORE);

- Freedom Riders: Joe Perkins, Jim Peck, Elton Cox, Dr. Walter Bergman, Jimmy McDonald, Charles Person, Ed Blankenheim, Genevieve Hughes, Albert Bigelow, Hank Thomas, Paul Brooks, Jim Swerg, and Salynn McCollum;

- Attorney General Robert Kennedy;

- Robert Kennedy’s aide, John Seigenthaler (to whom the second book was dedicated);

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.;

- Ralph Abernathy and his First Baptist Church;

- Fred Shuttleworth;

- Stokely Charmichael;

- A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters;

- Roy Wilkins of the NAACP;

- Whitney Young of the Urban League;

- Malcolm X;

- Bayard Rustin.

- Research, present, and discuss the lives and roles of those who violently opposed the Civil Rights Movement:

- Eugene “Bull” Connor;

- Alabama Governor John Patterson;

- Alabama Governor George Corley Wallace, Jr.;

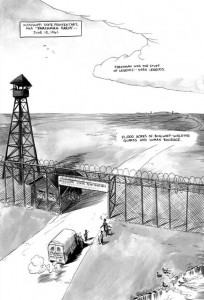

- Fred Jones, Superintendent Mississippi State Penitentiary (a.k.a. “Parchman Farm”);

- Mississippi Governor, Ross Barnett (1960 – 1964);

- South Carolina Senator Storm Thurmond;

- the Ku Klux Klan.

- Research, present, and discuss the different sides of the following

events that shaped the Civil Rights Movement. Discuss how each shaped

and affected the world around them:

- Theater protests in the 1960s;

- CORE’s Freedom Ride;

- The trial of E.H. Hurst, member of the Mississippi State Legislature who shot a local black farmer named Herbert Lee, and the resulting protest led by Bob Moses, Charles McDew, and Bob Zellner;

- The summer protest at the swimming pool in Cairo, Illinois, and the powerful photograph taken for the SNCC by Danny “Dandelion” Lyon;

- Protest march at Zion Hill Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on April 12, 1963, which was led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and led to his imprisonment and his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”;

- Jim Bevel and the SCLC’s Birmingham Children’s March on May 2-3, 1963.

- Read, evaluate and debate the merits and demerits of President Kennedy’s Civil Rights Bill, keeping in mind the social and political environments in which is was proposed.

- Read, evaluate, compare, and contrast the six speeches made at the March on Washington

- Analyze how the book’s different characters dealt with racism. Ask students how they might deal with racist comments, practices and restrictions.

- Discuss what it must have felt like to be excluded from busses, shops, and from receiving community services.

- Discuss different options and means of protest. How have these options changed today, if at all, compared to the options Lewis and his colleagues had in the 1960s?

- Research, present, and discuss the personal backgrounds, public struggles, and the articles and speeches of local and national figures of the Civil Rights Movement.

- Define and discuss “racism.”

- Discuss the different instances of discrimination and racism presented throughout the book. Discuss instances of racism today on local, national, and international scenes.

- How is racism the same / different across time and geographic locations (nationally and / or internationally)?

- How has racism changed today, if at all?

- Discuss how hurtful racism can be to those targeted as well as to the general population.

- Discuss how racism has influenced, shaped, and determined national and international policies and politics.

- Discuss what can be done today to fight racism and discrimination and ways students can help.

- On pages 96-97, Lewis notes that, “Racism in Mississippi was different than in Alabama… They tried to hide

the open violence that was so publicly allowed to take place in

Birmingham, Montgomery and elsewhere… Instead, much of the means of

enforcing segregation came through economic and political pressure

organized by a group called the White Citizens’ Council. Sort of like a

businessman’s Ki Klux Klan.”

- Research and compare the incidents and strategies of the White Citizen’s Council versus the Ku Klux Klan.

- Debate the effectiveness or the destructive qualities of each.

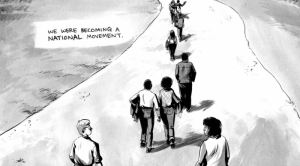

- On page 109, as the Freedom Ride campaign continued, Lewis writes, “By the end of the summer, dozens more busses carried the nation’s daughters and sons into the heart of the Deep South to carry on the work we began. The fare was paid in blood, but the Freedom Rides stirred the national consciousness and awoke the hearts and minds of a generation… We were becoming a national movement.” Discuss how and why national movements “become.”

- On page 114, Lewis notes that, “No state showed us what we were up

against more than Mississippi. Nearly 90% of the state’s black families

lived below the poverty line, and only 5% of eligible black voters were

registered….” Research and compare:

- The populations of various Black and White populations in Southern states in the 1960s and now.

- The populations and proportions of Black and White populations in Southern States that were registered voters.

- Discuss if / how things have changed and why / why not.

- Toward the end of the book, at the March on Washington, many had issues with Lewis’ original speech. As a result, he was pressured to cut out passages he felt quite passionate about. Discuss and debate the needs of compromise in public offices and speeches as well as in legislation.

- Search for, define, and discuss the book’s use of idioms, hyperbole,

and simile to better express opinions, feelings, and cultural

expressions. Discuss how effective they are in communicating a specific

message or a specific point in time. For example, you may want to

discuss:

- On pages 6-7, as the U.S. House Representatives line up for President Obama’s inauguration (2009), a colleague approaches John Lewis, telling him he should hurry to get to the front, and John Lewis replies, “There’s no need to hurry, I’ll end up where I need to be.” This then segues into Lewis’ past. Discuss the use of text and image to create this metaphor.

- On page 91, Lewis recounts Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s statement when explaining why he would not be joining the Freedom Riders, “…I think I should choose the time and the place of my Golgotha.”

- On page 99, “Parchman (Farm, Mississippi State Penitentiary) was the stuff of legends — dark legends. 21,000 acres of bullwhip-wielding guards and human bondage.”

- On page 109, as the Freedom Ride campaign continued, Lewis writes, “By the end of the summer, dozens more busses carried the nation’s daughters and sons into the heart of the Deep South to carry on the work we began. The fare was paid in blood, but the Freedom Rides stirred the national consciousness and awoke the hearts and minds of a generation… We were becoming a national movement.”

- On pages 140-141, in President Kennedy’s address, Lewis notes, “…The events in Birmingham and elsewhere have so increased the cries for equality that no city or state legislative body can prudently ignore them. The fires of frustration and discord are burning…It is time to act… A great change is at hand, and our task — our obligation — is to make that revolution, that change peaceful and constructive for all.”

- On page 171, in his March on Washington speech, Lewis notes, “By the force of our demands, our determination, and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces, and put them together in the image of God and democracy…”

- On page 172, Lewis notes about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech, “His words carried through the air like arrows… moving to a climactic refrain the world would never forget.”

- Compare and contrast the language used in the various speeches given at the March on Washington August 28, 1963.

- Have students collect family stories (oral, written, and / or

photographed) of the 1960s and the Civil Rights Movement, marches, and

protests, and / or stories of racism and segregation. [Note there were

and still are incidents of racism and segregation experienced by

minority and immigrant families as well. To include all your students,

you may want to expand your discussion to racist incidents directed at

various targeted groups.]

- You may have students write two versions of these stories as a means of reflecting on language use and idioms that are time or era specific.

- Have them write one version as if they are there in the 1960s, as a first-person narrative; and then writing it now, reflecting back. How does the language and the story differ?

Critical Thinking and Inferences

The authors make many inferences in this book both with language use and through imagery. You may want to discuss the following uses of inference:

- On page 22, Lewis recalls a conversation with the SNCC’s Central Planning Committee, debating whether nonviolent protests should be halted in response to the increasing violence that met them. Lewis notes that Reverend Will Campbell argued, “How can it be the right thing to do, to continue putting young people in harm’s way?” Lewis replies adamantly that they’re going to march regardless, and Campbell responds, “What it comes down to is that this is just a matter of pride to you. This is about your own stubbornness. Your own sin.” Debate the pros and cons on continuing non-violent protest when it’s met with violence, and discuss Campbell’s intent in what he said. Was he correct? Why or why not?

- Discuss the merits and intent of the Freedom Riders’ strategy (p. 36): “We will accept that arrest and if there is violence we will accept that violence without responding in kind We will NOT pay fines because we feel that, by paying money to a segregated state, we would help it perpetuate segregation.”

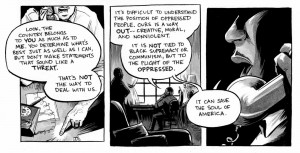

- Discuss Dr. King’s word to President Kennedy when he says (pg.95): “It’s difficult to understand the position of oppressed people. Ours is a way out — creative moral, and nonviolent. It is not tied to Black Supremacy or Communism, but to the plight of the oppressed. It can save the soul of America.”

- Discuss Dr. Martin Luther King’s intent when he wrote: “…I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law” in his Letter from Birmingham Jail.

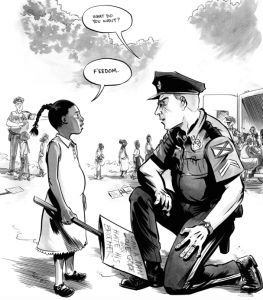

- At the Birmingham Children’s March on May 2-3, 1963, we see a police officer asking a young girl (p. 135), “What do you want?” She responds, “F’eedom.” Discuss Lewis’ comments as he notes, “It was an embarrassment to the city.”

In graphic novels, images are used to relay messages with and without accompanying text, adding additional dimension to the story. Compare, contrast, and discuss with students how images can be used to relay complex messages. Powell is a master at combining text, image, shading, and design work to communicate passions, events, and powerful messages. Here are lesson suggestions to help students learn and appreciate this skill:

- Have students hunt for examples of how Aydin and Powell use text,

image, and design to relay complicated messages and issues, or simply

present your own instances and have students analyze them. For example:

- Discuss how effortlessly the transitions are made between past and present. Analyze how this is done.

- On pages 70-71, Lewis relays how Attorney General Robert Kennedy arranged for the Freedom Ride to continue through Alabama. Evaluate and discuss how this is done through images, text, and panel design.

- On pages 79-82, the reader goes from the past, to the present, and then back to the past, with “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” sung throughout the transitions, adding multiple layers of meaning. Discuss how this is done and the intent of the authors in doing this.

- On page 115, Lewis recalls the incident in Liberty, Mississippi, where a local Black farmer, Herbert Lee, was shot dead by E.H. Hurst. Discuss how Powell’s use of gray on black relays the events.

- On page 123, discuss the powerful image in which Lewis is punched in the face with the text, “By the end of 1962, you heard people questioning whether SNCC should even BE a multi-racial organization.”

- On page 130 ,the authors relay a powerful passage from Dr. King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail. Discuss the use of black, white, and gray as well as the page design to brilliantly relay the lighter message of hope from the dark depths of prison.

- Have students hunt for visual and verbal examples of racism, discrimination, and / or segregation, comparing how they are relayed through language and how they are relayed through image. Discuss the impact of these various forms of communication.

- For parts of the story, Powell relays his images against a black background while others are relayed against a white background. Chart when he does each, and discuss why this might be. Discuss how page design and backgrounds help communicate the story and its messages.

- Compare and contrast how the authors help us distinguish between words that were sung, spoken, preached, and / or heard over the radio.

- Discuss how Powell uses art between pages 60-63 to relay the passage of time in Lewis’ life and narrative.

For greater discussion on literary style and/or content here are some prose novels and poetry you may want to read with The Silence of Our Friends

- March: Book One (August 2013): A graphic novel by Congressman John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell. This first volume spans Lewis’ youth in rural Alabama, his meeting with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the birth of the Nashville Student Movement, and their battle against segregation. NOTE: This book has an awesome teacher’s guide too.

- King by Ho Che Anderson (Fantagraphics, 1993; reprint edition 2010): A beautifully illustrated award-winning biography integrates interviews, narrative, sketches, illustrations, photographs, and collages that piece together an honest look at the life, times, tragedies, and triumphs of Martin Luther King, Jr. For King, Anderson won the Harvey Award for Best New Talent (1991), Best Graphic Album (1993), and Parents’ Choice Award (1995).

- The Silence of Our Friends by Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, and Nate Powell (First Second Books, 2012): A semi-autobiographical story of Mark Long’s childhood experiences in Houston, Texas, centering around the Texas Southern University student boycott after the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCCC) was banned from its campus in 1968.

- P.S. Be Eleven by Rita Williams-Garcia: Winner of the Loretta Scott King Award (2013) and sequel to One Crazy Summer (Newberry Honor Book) that reveals race, gender, and political issues of the late 1960s.

- I Have a Dream: Writings and Speeches That Changed the World by Martin Luther King, Jr.: Martin Luther King’s “ – text of his famous speech (see link below).

- Martin’s Big Words: The Life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by Doreen Rappaport and Bryan Collier (illustrator): An extraordinary picture-book biography incorporating narrative, famous quotes from Dr. King and powerful collage and watercolor illustrations introducing King’s words and legacy to younger readers.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

- March: Book One Teacher’s Guide can be downloaded at http://www.topshelfcomix.com/contact/teachers-guidehttp://www.topshelfcomix.com/contact/teachers-guidehttp://www.topshelfcomix.com/contact/teachers-guide

- PBS’ American Experience: Civil Rights Movement Non-Violent Protests — contains related videos, photographs, interviews, press coverage and primary sources, milestones, reflections, notes for teachers, and more

- Martin Luther King, Jr. I Have a Dream speech (text and audio)

- http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/themes/civil-rights/exhibitions.html — multimedia resources from the Library of Congress that support the teaching about civil rights

- Historical places of the civil rights movement — We Shall Overcome: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary with an introduction, itinerary maps, list of sites and links to learn more

- http://www.academicinfo.net/africanamcr.html — civil rights history resource

- http://www.pbs.org/teachers/thismonth/civilrights/index1.html — teaching ideas for teaching the civil rights movement in American literature (all grade levels)

- http://www.crmvet.org/poetry/poemhome.htm — poems of the Freedom Movement

- Notes and brochures of the SCLC’s Crusade for Citizenship found now at the King Center.

- For a more interactive link on the Freedom Rides, a production of “American Experience and PBS offers links retracing the route of the ride; first-person accounts of the rides through biographies, photos and film clips; a timeline of the events; and a discussion of the issues.

- Overview of the Freedom Rides from the History Channel

- Birmingham’s Children’s March via pbs.com with a video and outstanding audio reports (with detailed history background and personal testimonies and recollections of individual marchers) and additional links.

- Birmingham’s Children’s Crusade– Outstanding link with video and very powerful photos, background and personal accounts, and additional links by Kim Gilmore at biography.com

- PBS explores Project C and the Birmingham Campaign with photos and film clips; provides President Kennedy’s response to the violence in Birmingham, a segment on Birmingham and the Children’s March, and more.

- A transcript of President Kennedy’s press conference regarding “An Ugly Situation in Birmingham” May 1963.

- The History Channel’s interactive link on The March on Washington — With video clips of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, the March from Selma to Montgomery, background on the March on Washington, and information on how King’s speech became an impromptu addition.

- An Oral History of the March on Washington with interviews by Michael Fletcher and videos by Ryan R. Reed through Smithsonian.com

- A guide for students on how to conduct oral history interviews with samples of American slave narratives and other primary resource sets

- http://www.history.com/search?q=civil+rights+movement&x=0&y=0 – History channel list of links and resources

- http://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/civil-rights-movement and http://www.slj.com/2013/01/books-media/collection-development/focus-on-collection-development/civil-rights-everyday-heroes-focus-on-january-2013/ – provides extensive lists for further reading on the civil rights movement for students of varying ages and reading levels.

As always, thank you for your visit.

Please leave your own impressions or stories in the comments below.

-----

Meryl Jaffe, PhD teaches visual literacy and critical reading at Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth OnLine Division and is the author of Raising a Reader! and Using Content-Area Graphic Texts for Learning. She used to encourage the “classics” to the exclusion comics, but with her kids’ intervention, Meryl has become an avid graphic novel fan. She now incorporates them in her work, believing that the educational process must reflect the imagination and intellectual flexibility it hopes to nurture. In this monthly feature, Meryl and CBLDF hope to empower educators and encourage an ongoing dialogue promoting kids’ right to read while utilizing the rich educational opportunities graphic novels have to offer. Please continue the dialogue with your own comments, teaching, reading, or discussion ideas at meryl.jaffe@cbldf.org and please visit Dr. Jaffe at http://www.departingthe text.blogspot.com.

All images (c) John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell.

I saw John Lewis on the Daily Show on March 9, right after the Selma weekend. A glorious man. He talked about the books, which seem wonderful.

ReplyDeleteWow! A very MEATY contribution to ABC Wednesday!

ReplyDeleteDenise ABC Team

I have yet to read the book but have heard many interesting things about it. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteHave a great rest of the week and happy Easter.

I really like you post.I would like to share page collection with you!

ReplyDeleteสมัครบาคาร่า

https://saglamproxy.com

ReplyDeletemetin2 proxy

proxy satın al

knight online proxy

mobil proxy satın al

6Y638

https://saglamproxy.com

ReplyDeletemetin2 proxy

proxy satın al

knight online proxy

mobil proxy satın al

KKGNDH