I have been asked to post an article I wrote on "Graphic Novels and Critical Thinking: A Piagetian Approach."

As this is much longer than my typical posts, I have provided an

outline overview and headed each section in bold, capital letters to

help you better navigate, skim, and collect the information you seek.

|

| From: copyblogger.com |

This article:

- Defines Critical Thinking

- Relates Piaget's Theory of how we all must

CONSTRUCT levels of understanding as we evaluate, relate, and analyze

information in front of us - helping us gain greater and more effective

levels of understanding

- Relates how graphic novels can play an integral

role in critical thinking, analytic thinking, inference making,

sequential thinking and help students grapple with abstract concepts

such as metaphor.

- Provides tables and materials you can reproduce to help students with critical thinking

- Provides suggested graphic novels suggestions for various learning levels and learning issues.

I. CRITICAL THINKING - A WORKING DEFINITION:

"Critical Thinking...is the intellectually

disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing,

applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information

gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection,

reasoning, or communication." -M. Scriven & R. Paul, 8th Annual International Conference on Critical

Thinking and Education Reform, Summer 1987

Critical thinking leads to intellectual independence.

Memorize the solution to a problem, and one has the key to that

particular problem, understand and critically evaluate underlying concepts to effective solutions and you'll develop the tools to

create your own effective solutions to a multitude of diverse problems.

When

we're willing and able to acknowledge our own capability as thinkers

and acknowledging our strengths and weaknesses this allows us to refine

our thought process so that we learn to think and process information more

effectively and comprehensively, rejecting false/incomplete

'constructs' and ideologies while building more accurate ones.

This is where Piagetian theory comes in

(and developed further below). To grow as critical

thinkers, he posted that we must constantly reevaluate our 'schemas' or ideas checking

our 'knowledge' with evidence, making sure they fit and that there is

no incongruousness. Furthermore, we must be willing to refute (often)

cherished ideas if there are too many inconsistencies between our

'knowledge' and available evidence.

Reasoning and critical thinking plays an intrinsic role in our decision making and judgement formation.

II. KIDS' CRITICAL THINKING...WHERE GRAPHIC NOVELS COME IN:

|

| From: austhink.com |

Abstract

concepts such as inference, metaphor, and social context are often

difficult concepts for students to comprehend. They are usually taught

through classroom discussions, which pose a distinct challenge for

visual learners, for students with weak language skills, or for concrete

learners with weak higher-order cognitive skills. Graphic novels can help by providing visual as well as verbal cues, concrete use of metaphor, and more motivating and natural opportunities for building inference and scaffolding comprehension.

Graphic novels

offer motivational and visual components making many concepts easier to

grasp (Edwards, 2009; Lyga, 2006, Gorman, 2003). They also provide

verbal and visual cues that aid comprehension for visual learners, while

reinforcing them for verbal learners (Crilley, 2009; Schwarz, 2002).

From a Piagetian perspective, graphic novels' sequential art panels

deftly integrate verbal and visual dialogue and background that the

reader (and author/artist) melds to construct the story. Between the

panels of story, are pauses or spaces ("gutters") over over which the

reader must navigate and infer what is happening between the panel

sequences. When reading graphic novels, readers continuously combine

visual and verbal data to construct meaning, intent, mood and movement

over (often unspecified) periods of time.

III. A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF PIAGET'S THEORY OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

While

many educators are aware of Piaget's stages of Cognitive Development,

what appeals most to me is his epistemological theory of how children

learn, develop, and construct levels of understanding:

Learning, for Piaget (1976) IS critical thinking (although he didn't use those words).

It involves a dynamic, active process. When we are exposed to new

information and it makes sense to us (based on our existing

understanding or 'knowledge' of the world and the information in front

of us), the new data will be "assimilated" or incorporated into our

existing 'schema'. IF, however, we are exposed to something that does

not make sense, we enter (an uncomfortable) state of 'disequilibrium' which we try to manipulate and work it out until it does make sense. We

will either ignore the information we can't understand and critically

analyze, OR construct rules or 'schema' to 'accommodate' the new data.

Sometimes the newly generated rules or theories are valid and will hold

over time, sometimes they will not.

Piaget

refers to this process of taking information and integrating, tweaking,

and altering existing 'knowledge' to 'fit' the new data (and reach a

new state of equilibrium) as accommodation. Generating knowledge,

for Piaget, is a fluid, active and constructive process. This is

because we are constantly interacting with the world around us, noticing

glitches of understanding and working them out so the world makes sense

on a keener, more efficient level.

Let's revisit Piaget's classic experiment with volume to illustrate how children learn: There are two clear containers - one is tall and thin (Vase A), the other shorter and wider (Vase B):

Vase A

Learning, for Piaget (1976) IS critical thinking (although he didn't use those words).

It involves a dynamic, active process. When we are exposed to new

information and it makes sense to us (based on our existing

understanding or 'knowledge' of the world and the information in front

of us), the new data will be "assimilated" or incorporated into our

existing 'schema'. IF, however, we are exposed to something that does

not make sense, we enter (an uncomfortable) state of 'disequilibrium' which we try to manipulate and work it out until it does make sense. We

will either ignore the information we can't understand and critically

analyze, OR construct rules or 'schema' to 'accommodate' the new data.

Sometimes the newly generated rules or theories are valid and will hold

over time, sometimes they will not.

Piaget

refers to this process of taking information and integrating, tweaking,

and altering existing 'knowledge' to 'fit' the new data (and reach a

new state of equilibrium) as accommodation. Generating knowledge,

for Piaget, is a fluid, active and constructive process. This is

because we are constantly interacting with the world around us, noticing

glitches of understanding and working them out so the world makes sense

on a keener, more efficient level.

Let's revisit Piaget's classic experiment with volume to illustrate how children learn: There are two clear containers - one is tall and thin (Vase A), the other shorter and wider (Vase B):

Vase A

Vase B

Vase B

If you were to fill each vase with one cup of water and ask a child: "Which has more liquid?"

- Vase A

- Vase B

- They have the same amount

A young child (typically below the age of six) will tell you that Vase

A has more. If you were to ask her why, she would tell you that the

water is 'higher' in vase A so it has more. Piaget would then have her

measure ONE CUP of water (again) on her own into each vase, making sure she 'knows'

that each vase had one cup of liquid. he would then ask the same question and see if

the child can critically evaluate and incorporate the 'data'.

Inevitable, the young child will continue to respond that 'A' has more because kids (typically under age six) think very concretely

focusing ONLY on the most obvious aspect of what they "see." In this case they see that in Vase A

the water level is higher and therefore must be "more." The young child will not assimilate the fact that Vase B is wider and as a result the same amount of liquid spreads out more, making the water level look lower.

When kids can go beyond the visual (or concrete)

and concentrate on more than one obvious aspect of a problem at a time

(somewhere between six and eight years), they will respond differently.

At first they may say that Vase A has more water, but when asked to

carefully remeasure "one cup" of liquid into each vessel, they will recognize that 'A'

may not have more more water - they just measured one cup for each Vase. At this point the child is reaching a state of disequilibrium. She knows she filled both vases with the same amount of liquid, but one clearly looks like more.

This state of disequilibrium

is a gold-mine for teachers. The goal at this point is to ask the child

questions that help focus NOT ONLY on the obvious (the liquid's

height), but to consider integrating various aspects of the problem

simultaneously. In this case the student must consider the length,

height, and width of both vessels to correctly analyze the

problem. Successful responses require visual and mental integration of

multiple aspects of the problem. The more the student physically,

visually, and cognitively manipulate the problem, the sooner

they'll arrive at the solution. This is what critical thinking is all

about - integrating multiple aspects and modalities of a problem to

arrive at an effective solution.

Graphic novels fit into this mode of learning because in order to 'comprehend' and integrate the story, readers must go beyond one source or the 'obvious'. They must intergrate the words, color, page arrangement, visual details - the subtle and the obvious.

IV. GRAPHIC NOVELS' UNIQUE ROLE IN CRITICAL THINKING, CONSTRUCTING AND SCAFFOLDING "UNDERSTANDING"

|

| From: plpnetwork.com |

While

readers of poetry, prose, and graphic novels all construct knowledge as

they read, graphic novels offer a unique format and opportunity to

scaffold and "build" information. When reading graphic novels, readers

must construct the meaning of each panel using color, language,

illustration details, facial expressions, text size, text font, and

shading (McCloud, 1993). In essence, graphic novels provide multiple

'practical aids' to scaffold, build, integrate, and facilitate comprehension.

Graphic

novels' gutters offer natural breaks where readers can pause to

evaluate comprehension and make inferences about what is happening both

within and between the panels. Furthermore, graphic novels provide both

verbal and visual information aiding comprehension and critical

analysis. So, for example, to determine mood, readers can look at the

colors used by the illustrator, at the characters' facial expressions,

at the fonts used, the text, even the types of borders used to enclose

the panels. Even the panels' arrangement on the page provide valuable

information the reader must use to actively construct and infer the

complete story. This is particularly useful for students with language

weaknesses.

How can graphic novels help stimulate cognitive growth?

Let's look at a language arts class, for example: The students are reading Robert Frost's poem The Road Not Taken

and one student, let's call her Cora, cannot understand why Frost

commented about this poem that "You have to be careful about [this] one:

It is a tricky poem - very tricky." To concrete and literal readers

like Cora, they think he is simply walking in the woods and has to

decide what path to take. They don't necessarily understand

'metaphor', the issue of 'opportunity costs', conflict, or long range

decisions.

Here is a LESSON SUGGESTION INTEGRATING GRAPHIC NOVELS WITH ROBERT FROST'S THE ROAD NOT TAKEN:

- Read Frost's poem. Analyze it and deconstruct its metaphor

- Ask students to create an

additional stanza in Frost's style continuing the metaphor OR simply

have them deconstruct the metaphor - either as homework or in smaller

group work. Maybe this stanza can be an 'afterward' reflecting after some time passed. [In doing so, they not only have to understand the poem,

they have to understand its intent and style.]

- In

small groups have students read their stanzas or deconstructions to

each other, and be prepared to summarize and present their work to the

class as a whole. [Working in groups will provide additional

opportunities for students to check each others' understanding and build

from what they know.

- Have

each group present their summaries, select the class' favorite final

stanza or metaphor deconstruction - making sure to critically evaluate

WHY it is their favorite, WHY it is the closest approximation to what

Frost might have written.

- Bring in graphic novels to support/reinforce

'metaphor' and critical reading of the text. What makes graphic novels

so powerful is that the format alone forces students to go beyond the

literal, and the stories and graphic novels themselves are often

visual/verbal metaphors. SEE GRAPHIC NOVEL OPTIONS AND DETAILED LESSON

SUGGESTIONS BELOW.

- When incorporating the graphic novels, the key

is to help them practice understanding and building inferences, metaphor

and comprehension.

- As a final follow-up lesson

component to EVALUATE student progress or to REINFORCE inference-making:

read and discuss other poems or prose novels with heavy use of metaphor. Dylan

Thomas' "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night" and Frost's "Nothing Gold Can Stay" are excellent companion poems. Prose novel companions suggestions that are full of metaphor and allegory are The Gammage Cup (for middle school students) and To Kill a Mockingbird, The Grapes of Wrath or The Outsiders (for older students).

- Another final alternative might be to

have the class rework Frost's poem as a work of sequential art. This

would require them to understand the intent and abstract concepts as

well as the literal 'story' and break them down into concrete,

sequential panels. They would have to make concrete choices about mood

and metaphor while constructing and communicating ideas verbally and

visually - integrating multiple aspects of the assignment into a

cohesive final product.

IV. THREE GRAPHIC NOVEL

LESSONS TO BE USED WITH OR WITHOUT THE POETRY COMPONENT ABOVE TO

CONTINUE TO BUILD CRITICAL READING AND ABSTRACT THINKING

A note on selecting

graphic novels for classroom use: Always

read the graphic novels before using them in the classroom. We work in different locations with

different tolerances and agendas.

You know your students better than anyone else. You know what they will relate to,

enjoy, and comprehend. Also, most

publishers do not specify age levels for their books. One reason for this is that they can be used and read with

different goals by various ages. Also

note that some graphic novels present complete,

self-contained stories, while others are parts of (often ongoing) series

with minor resolutions. Both are

useful. For further graphic novel

suggestions, see Monnin, Teaching Graphic

Novels: Practical Strategies for

the Secondary ELA Classroom (2010); Carter’s Rationales for Teaching Graphic Novels (2010), Gorman’s “Graphic

Novels Rule! The Latest and Greatest for Young Kids” (2008), Gutierrez “Good

& Plenty: It Used to Be Hard

to Find Good Graphic Novels for the k-4 Crowd” 2009); Weiner “Show, Don’t Tell: Graphic Novels in the Classroom”

(2004); and Terry Thompson, Adventures in

Graphica: Using Comics and Graphic

Novles to Teach Comprehension, 2-6 (2008).

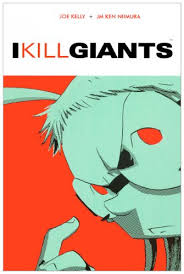

I chose the three books below for various reasons: I Kill Giants is an extremely powerful

story and is easy to relate to as Joe Kelly brilliantly weaves metaphor and

conflict in and out of his story. What I like about Laika is that it presents a slice of history as it tells of the

Soviet race to space, and can be used with a slightly younger audience. It is also a story that cannot have

been as effectively told in prose, which is a wonderful discussion point on its

own. Finally, TRIBES: The Dog Years, is a feast for the eyes with its incredibly creative use of page, color and art, and its

powerful social messages were just too hard for me to resist it. It does, however, contain violence and

is not appropriate for all classes. It is a great companion read for Lord of the Flies.

Check it out though; it is worth the look. Note that these books

selected are for middle and upper school students.

GRAPHIC NOVEL LESSON - OPTION1: KILL GIANTS by Joe Kelly I(for grades 6+):

Brief Synopsis: I Kill Giants by Joe Kelly illustrated (in black and white) by J. M. Ken Niimura, is

about a fifth grade girl wrestling with social and personal issues. We learn right away that Barbara kills

giants, but the reader is not sure whether this is real or fantasy. Barbara’s home is dark and mysterious.

She herself is ‘different’ and a loner, with one friend - a new girl,

Sophia. Barbara teaches Sophia all

about giants: their threats as well as their mythological origins. Initially while reading, the reader is constantly

‘guessing’ what really is going on and only later learns who and

what the “giants” actually are, why Barbara must face them, and how she

eventually overcomes them. Rich vocabulary, references to mythology, metaphors,

illustrations and sensitivity abound. There is some mild profanity.

Brief Synopsis: I Kill Giants by Joe Kelly illustrated (in black and white) by J. M. Ken Niimura, is

about a fifth grade girl wrestling with social and personal issues. We learn right away that Barbara kills

giants, but the reader is not sure whether this is real or fantasy. Barbara’s home is dark and mysterious.

She herself is ‘different’ and a loner, with one friend - a new girl,

Sophia. Barbara teaches Sophia all

about giants: their threats as well as their mythological origins. Initially while reading, the reader is constantly

‘guessing’ what really is going on and only later learns who and

what the “giants” actually are, why Barbara must face them, and how she

eventually overcomes them. Rich vocabulary, references to mythology, metaphors,

illustrations and sensitivity abound. There is some mild profanity.

One of my favorite quotes:

“With respect, Principal Marx…until you’ve actually fought a

giant…until you’ve looked into its eyes and seen the horrors that crawl behind

them...you really have no right to judge me.” (p.11)

How can I Kill Giants help students like Cora? The book is actually one long metaphor

about how we all must face our own personal giants, and leads the reader to

clearly understand the intent and awesome power of 'metaphor'. It is also a personal story that will be real and meaningful

to your students. The more they

relate to it, the easier it will be to make inferences and abstract intent. The really powerful discussion tool for

inference building is that while Barbara does not actually kill the physical

giant, she does face and kill her personal, social and emotional giants. So, the question to your class is:

“What giants does Barbara kill in this story?”

Suggestions for

I KILL GIANTS Classroom use:

- Barbara discusses Titans and giants. You may want to tie this into a

mythology class – discussing literal types of giants. Then move on to the use of giants in metaphor and allegory.

- Towards the end of Chapter 2, we see Barbara

with an armored helmet, visor and breastplate waiting (for the bus?). A fairy imp is huffing and puffing

around her and she tells him, “No one’s there you don’t have to hide.” He responds, “Oh really, miss tall and

steely? You’re hiding.” She responds, “I’m not.” Discuss the literal and figural intent

of “hiding.” What does the imp

think she’s hiding from? Why does

she not admit she is hiding? You

can also discuss sarcasm – it’s use and intent. Finally, this interchange occurs on the last two pages of

the chapter. Discuss how Kelly

uses this to keep the readers’ interest up until the Chapter 3 (note this was

originally seven separate comics until published as one graphic novel.)

- There

is a lot of anger and some violence (kids fighting out of anger, fear, and

frustration). This is an excellent

vehicle to discuss anger, anger management, bullying, and social cognition –

how best to read and interact with the people around you.

- In

Chapter 3, there are frequent occasions where the dialogue is crossed out. What

do readers think was crossed out and

why is it crossed out? (This is another opportunity to discuss inference,

intent, and denial).

- Barbara

discusses harbingers. What are the harbingers that usher in the Titan? What are harbingers for the seasons and

storms? What are harbingers of

disease and death?

- Discuss

the Titan’s words to Barbara: “…I did not come for herrrrr… I came for you,

child… All things that live, die.

This is why you must find joy in the living, while the time is yours,

and not fear the end. To deny this

is to deny life. To fear this…is

to fear life… You are stronger than you think.”

- Pair this novel with any prose novel or poem and

compare and contrast the authors’ use of metaphor and use of language.

GRAPHIC NOVEL LESSON - OPTION 2: LAIKA by Rick Abadzis (for grades 5+):

Brief Synopsis: Laika by Rick Abadzis, is the story of

the first dog (and sentient being) hurled to space and describes a segment of

the Soviet space race in the 1950’s.

The reader relates not only to Laika, but to all the people she touched

during her short, difficult life. Both verbal and visual stories are told in a

simplified style. The colors used

in the cartooning are predominantly earth tones – except for: (a) moments of

great importance (or foreshadowing) when they become bright, vibrant and more

three-dimensional, and (b) dream sequences where the panel lines grow soft and

colorful. The panel on page143,

Laika’s trainer, Yelena, learns Laika will not be returning, and this is the only panel where we see a person’s

shell with no facial features drawn.

The art it is an important aspect of the book, and one that should be

discussed with students when talking about intent and inferencing. Finally, the book contains a powerful

final quote from Oleg Georgivitch Gazenko, one of the main characters, as well

as an extensive bibliography of books, videos and online sources that can be

used with the book.

How can Laika help a kid like Cora? Aside from the discussions suggested

below which help guide students from the concrete story (and illustrations) to the

author’s intent, Laika has the added

benefit of representing characters who say one thing, but whose expressions and

body language relate something else. This creates a sense of disequilibrium and is a very

powerful tool when discussing social cognition and the art of social

interactions. This graphic novel is also an excellent way to introduce the Cold War, the space race, and October Sky by Homer Hickam.

Brief Synopsis: Laika by Rick Abadzis, is the story of

the first dog (and sentient being) hurled to space and describes a segment of

the Soviet space race in the 1950’s.

The reader relates not only to Laika, but to all the people she touched

during her short, difficult life. Both verbal and visual stories are told in a

simplified style. The colors used

in the cartooning are predominantly earth tones – except for: (a) moments of

great importance (or foreshadowing) when they become bright, vibrant and more

three-dimensional, and (b) dream sequences where the panel lines grow soft and

colorful. The panel on page143,

Laika’s trainer, Yelena, learns Laika will not be returning, and this is the only panel where we see a person’s

shell with no facial features drawn.

The art it is an important aspect of the book, and one that should be

discussed with students when talking about intent and inferencing. Finally, the book contains a powerful

final quote from Oleg Georgivitch Gazenko, one of the main characters, as well

as an extensive bibliography of books, videos and online sources that can be

used with the book.

How can Laika help a kid like Cora? Aside from the discussions suggested

below which help guide students from the concrete story (and illustrations) to the

author’s intent, Laika has the added

benefit of representing characters who say one thing, but whose expressions and

body language relate something else. This creates a sense of disequilibrium and is a very

powerful tool when discussing social cognition and the art of social

interactions. This graphic novel is also an excellent way to introduce the Cold War, the space race, and October Sky by Homer Hickam.

Suggestions for using LAIKA in the Classroom:

- Discuss the influence of color and drawing on

the story and perspective. How

does the use of color and lines reflect mood and intent? Why, for example, on

page 143, did Rick Abadzis decide to leave Yelana’s face stone white with no

facial features what so ever? Is this a form of visual metaphor? What is the author’s message to the

reader?

- Throughout this book, the characters say one

thing, while their facial expressions infer other intents and emotions. Why

might these characters want to hide their emotions?

- Have students write dialogue that reflect the

facial expressions. Discuss how the story might have been different had the

characters expressed their true feelings.

Discuss how important it is, in any situation, to read and match what is

said in words, with what is said in expressions and body language. This is very important in developing

social cognition.

- You may want to read this book in conjunction

with Homer Hickam’s October Sky. Each book portrays the space race from

very different perspectives.

Compare and contrast the format, the cultural nuances and the stories. You may, for example, want to read the

book and then assign chapters to students or group of students to create an October Sky graphic novel.

- In the beginning of the book, a young boy’s

mother is convinced that taking care of a puppy would teach him responsibility. The boy, however, does not want a puppy. Brainstorm/debate

the pros and cons of whether he should be forced to take care of a dog; problem

solve alternative modes to teaching responsibility.

- Discuss Gazenko’s final quote and how it relates

to animal right’s movements: “Work with animals is a source of suffering to all

of us. The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We did not learn enough from the

mission to justify the death of the dog.”

- If/ when discussing the cold war bring in the

panels on page21 where Premier Khruschev pushes Korolev (Sputnik’s director) to send Sputnik II

up in one month’s time because he wants to, “show the whole world the

advantages of socialism!” This is

a very powerful, important sentence, one well worth delving into. Have students infer what he means by

this:

"How would sending a second satellite up in one month’s time (on the 40th

anniversary of the Revolution on November 7th) send a message

of socialist prowess? You may want

to research whether, in fact, this was effective. What types of visual and

verbal images support the Premier’s intent?"

GRAPHIC NOVEL LESSON - OPTION 3: TRIBES: THE DOG YEARS by Michael Geszel and Peter Spinetta, art by Inaki Miranda (for grades 5+):

The final book I will discuss is TRIBES: The Dog Years.

It is ONLY for older students as it has some violence. It does, however, have excellent points

for discussion. TRIBES: The Dog Years by authors Michael Geszel and Peter Spinetta

and artist Inaki Miranda is truly a feast for the eyes and mind. While there is more violence in this

graphic novel than the others, the art, print and format are so inviting and

creative. The power of using this, aside from the

social message (which I will get to in a minute) is for the sheer creativity it

inspires.

The power of TRIBES’ Art: The pages are presented

horizontally and the art tells as much if not more of the story than the verbal

prose. In addition, the panels

merge, expand, and contract in a life of their own, providing additional cues,

rhythm, and story-telling opportunities.

The art has exceptional detail and depth, and while set in the future,

it has a strong connection to the past. Take page fifteen, for example:

The character’s clothes are, in fact, remnants from our

culture. One character (above) has

a “one way” arrow across his shirt. Another character’s shoulder pad is

actually half a football (not shown on this page). Also notice the unique use of panels and inserts to help

focus the reader’s attention. On this page, for example, we see and read about

the character’s interactions and reactions, while noticing the scope and

details of their village and culture – both essential for understanding the

tribe and its role in the story.

Furthermore, the colors and styles of the visual story

change as the story changes. While

the book opens with tribes of kids who are survivors of a nano-tech virus and

must live primitively in harmony with the earth, the illustration’s colors are

primarily vibrant earth colors.

They change, however to whites, grays and blues as the characters

journey to the laboratories of the previous technological society.

The power of TRIBES’ plot:

The story opens in the year 2038 to a world recoiling from a

nano-tech virus that caused the “dog years” and reduced human life span to

twenty-one years. As a result,

civilization as we know it collapsed as did the cities, states and

nations. In 2038, civilization is

organized in tribes. Volume One

begins by introducing the Sky-Shadows who hunt and gather, and are at peace

with the earth. They fear the

Headhunter tribe (who, unfortunately are cannibals- but please don’t let this

turn you off – just think of Lord of the Flies - which I suggest

using as a prose novel to pair with this one – as discussed below). One day, the protagonist, Sundog (a Sky

Shadow), is keeping watch and notices a helicopter crash nearby. The lone survivor is an “Ancient” (in

his fifties) who convinces Sundog of his quest to reverse the “dog years” and 21-year

age ceiling caused by the virus. While the literal story is about the quest to

develop an antibody for the virus, there is a strong message about community

and governance, medical ethics, and environmental issues. This book can be used to introduce and reinforce issues such as medical ethics, role of science and technology, and the role and function of government.

Suggestions for TRIBES: THE DOG YEARS Classroom use: This is a book that can be used in its entirety or in sections. You may, for example, want to only use

sections of and fill in the rest of the story yourself. Here are a few

topics for discussion:

- Even the first few pages with little to no

written text can be used for inference building. They show Sundog and the Sky Shadows on a hunt. You can use this as a discussion of the

art, use of panels, and on the role of hunters and community in the Sky Shadow

tribe.

- Discuss the breakdown of civilization when there

is no infrastructure, no rules to follow and/or limited means to enforce them. Pair the story line and presentation of

Tribes: The Dog Years with Lord

of the Flies.

- Discuss the very different ways and the pros and cons of how the tribes decided to govern themselves.

- There is a lot of discussion about “quantum

batteries” and about medicine and scientific research in search of cures. Discuss roles of regulation, research

design, and the responsibility of researchers in protecting populations. When discussing the role of scientific

research and responsibility, you may want to compare this story to Mary

Shelley’s Frankenstein.

- There are flashbacks to Los Angeles and the

immediate aftermath of the virus.

In particular there is illusion to an epic battle in Dodger

Stadium. Compare this battle to

other epic battles such as those in the Illiad.

V. CONCLUSION:

My intent has been to spark a discussion on how graphic

novels can be integrated into your curriculum to help encourage and direct the

development of abstract thinking, inference making and social cognition. With

motivating and inviting art, with the pairing of visual and verbal cues, and

with natural pauses to reflect and make inferences, graphic novels are uniquely

suited to help aid in teaching and making inferences, advancing creative

thinking and problem solving, and in promoting both visual and verbal

fluencies.

Research has shown that some teachers fear graphic novels are

too ‘risky’ to include in the curriculum (Carter, 2009) while others,

unfamiliar with the quality work produced lately, believe comics and graphic

novels are ‘junk’ literature (Galley, 2004) and have no place in the classroom

(I used to be one of them). Others

are just not familiar enough with this format to comfortably include graphic

novels in their lessons or their classroom libraries. This however, is changing

and I hope to have added my voice and support to this discussion.

Using graphic novels to support poetry and prose novels is motivating and involves visual learners.

use it to introduce complicated abastract issues and concepts (metaphor, role and funcition of government, ethics, role of science and technology, history, etc.) It is an excellent means of using illustrations to explain and

reflect abstract concepts and issues and for breaking down social nuances teaching

students to ‘read’ and understand facial expressions and the use of verbal and

nonverbal communication skills. Incorporating graphic novels in the classroom is

also valuable for helping students recognize sequential components to a story

while building inference and vocabulary skills. Finally, it reinforces multimodal learning and helps teachers

reach and motivate more students.

REFERENCES

Bitz, M. (2009).

Manga high: Literacy, identity, and coming of age

in an urban high school. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard Education Press.

Carter, J. B. (2010). Rationales

for teaching graphic novels. Gainesville,

FL: Maupin House.

Carter, J. B.

(2009) “Going Graphic” Educational

Leadership March 2009, Vol. 66 Issue 6, pp.68-72

Carter, J. B. (Ed.) (2007). Page by page, panel by panel: Building literacy connections with

graphic novels. Urbana, IL:

NCTE.

Crilley, M. (2009). Getting students to write using comics. Teacher Librarian, 37(1).

Geszel, M. and Spinetta, P. (2010) TRIBES: The Dog Years. San Diego, CA: IDW Comics.

Gorman, M. (2008).

“Graphic Novels Rule! The latest

and greatest for young kids. School Library Journal, 54(3), 42-48.

Guteirrez, P. (2009) “Good & Plenty: It used to be hard to find good graphic

novels for the k-4 crowd.” My, How

Times Have Changed. School Library Journal, 55(9), 34-39.

Hinton, S.E. (1965) The

Outsiders. New York: Viking

Press, Dell

Kelly, J. & Niimura, J. M. K. (2009). I Kill Giants. Berkeley, CA: Image Comics.

Kendall, C. (1959) The

Gammage Cup. New York: Odyssey/

Harcourt Young Classic, Harcourt, Inc.

Lee, H. (1960) To Kill A Mockingbird. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott &

co.

Lyga, A. (2006) “Graphic novels for (really) young readers: Owly, Buzzboy, Pinky and Stinky. Who are these guys? And why aren’t they ever on the shelf? School

Library Journa,l 52(3). 56-62.

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding

Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Collins.

Monnin, K. (2010) Teaching

Graphic Novels: Practical

Strategies for the Secondary ELA Classroom. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House.

Schwarz, G. E.

(2002). “Grapic novels for

multiple literacies.” Journal of

Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46, 262-65.

Thompson, T.

(2008). Adventures in Graphica: Using comics and graphic novles to

teach comprehension, 2-6.

Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Weiner, S. (2004.)

Show, Don’t Tell: Graphic novels

in the classroom. The English Journal. 94(2). 114-117.

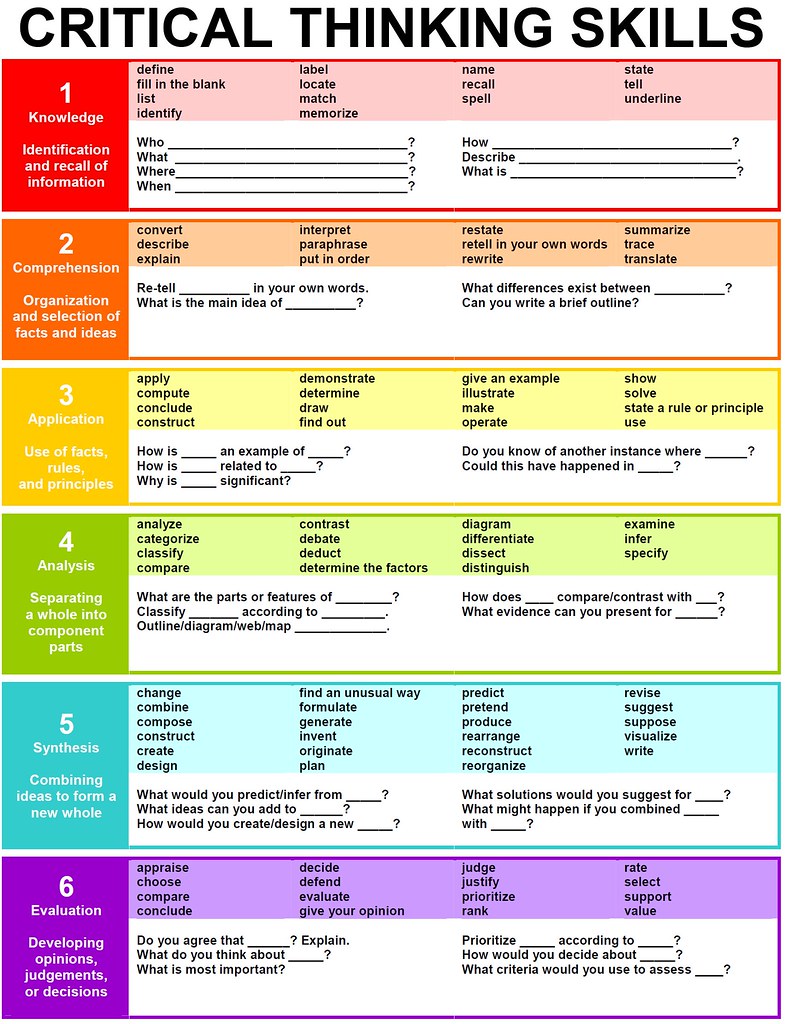

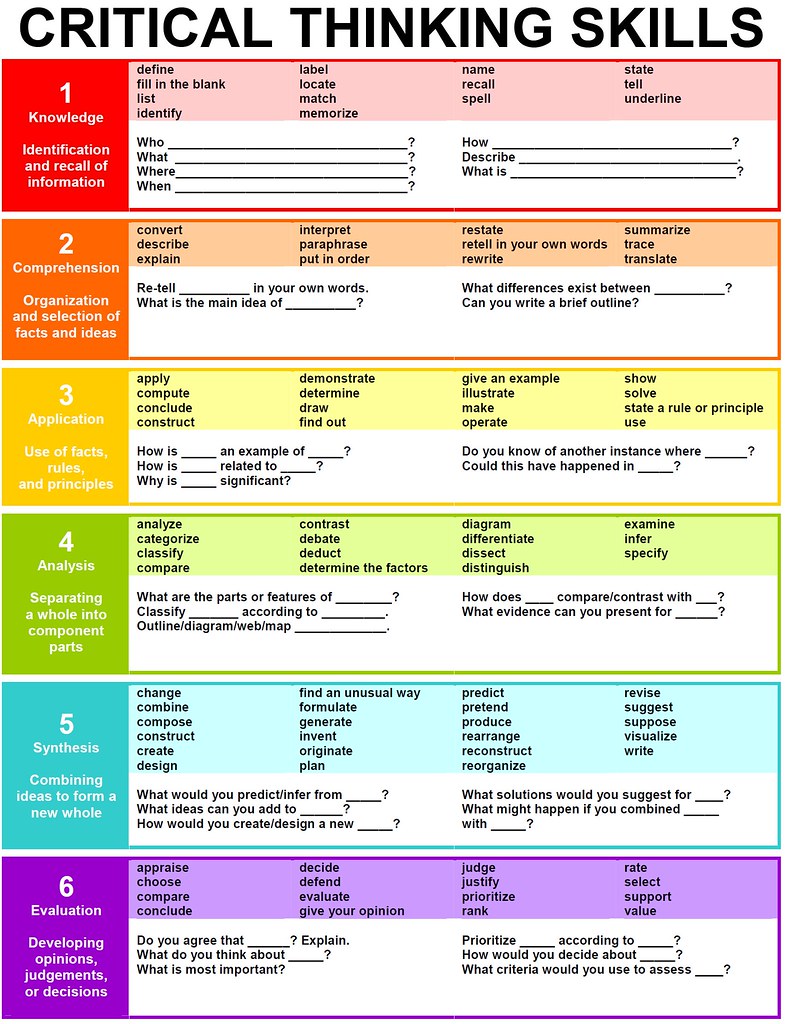

As an addendum, here is a wonderful reproducable chart you can use to help your students develop critical thinking skills...Definitely NOT Piagetian, but helpful nevertheless:

|

| From: http://www.flickr.com/photos/vblibrary/4576825411/sizes/l/in/pool-27724923@N00/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thank you for your time and visit. I would love to hear your reactions and suggestions in the comments.